When you think about history, you probably picture cannon fire, the clashing of empires, or dusty maps redrawn by colonisers. You might even hear the echo of battlefield drums ringing in your ear.

But History PhD student Ruizhi Choo hears something else entirely: the buzzing of insects — the tiny, often-overlooked creatures that have endured and evolved through centuries of human conflict and environmental change.

He tunes into insects — yes, insects.

More specifically, he’s digging into the role these creepy crawlies played during Malaya’s colonial period; how they were moved around, managed, and sometimes feared by imperial powers. And it turns out, their tiny footprints left a massive ecological legacy.

“Insects are a way to understand environmental change during colonialism,” Ruizhi explains. “They help us see how colonial policies shaped the landscape, and how those changes still affect us today.”

Ruizhi on a visit to the University of Wisconsin-Madison to attend intensive Indonesian classes as part of his PhD in History. Source: Ruizhi Choo

A PhD in History… to study insects?

Sounds out there, right? But there’s a method to this.

Let’s rewind.

In 1511, the Portuguese captured Malacca, kicking off centuries of European colonial involvement in the Malay Peninsula. Then came the Dutch in 1641, followed by the British, who made their move in Penang in 1786.

All that empire-building reshaped entire ecosystems.

“They cleared rainforests to grow cash crops like coffee, rubber, and coconuts,” Ruizhi says. “That created new environments and new food sources for insects.”

The colonial officers were benefiting greatly from this (financially, of course), but there was a problem — insects started eating up the “cash crops”.

Cue panic from colonial officers. The very insects they weren’t bothered about (or unwillingly transported across oceans) began feasting on these money-making crops.

Colonial administrators documented their battles with bugs, thus leaving behind a pile of historical records.

“Their anxiety became our archives,” Ruizhi says. “They wrote a lot of reports, letters, notes, and that’s what I study. You can track how the environment changed just by looking at how they talked about insects.”

As part of his History PhD, he is affiliated with the East-West Centre. Source: Ruizhi Choo

Ruizhi is trying his best to help people understand the importance of insects and history.

Pesky they can be, they were key to the advancement of public health, colonial anxieties, and the long-term consequences of empire.

“Mosquito-borne diseases changed how people lived in colonial Malaya,” he says. “That, in turn, justified more colonial control — new laws, urban planning, even who could live where.”

The history of insects matters

Sure, insects might not seem like the most glamorous subject for a PhD in History.

“[But] when we only focus on leaders and wars, we miss out on the everyday lives that make up history,” he says. “Insects give us a window into how people lived, and how they coped with change.”

And in a world facing climate crisis, biodiversity loss, and uncertainty in seemingly everything, understanding how humans and insects have shaped each other across time suddenly feels very timely.

Because sometimes, they buzz, bite, and leave itchy reminders of the past and people then survived.

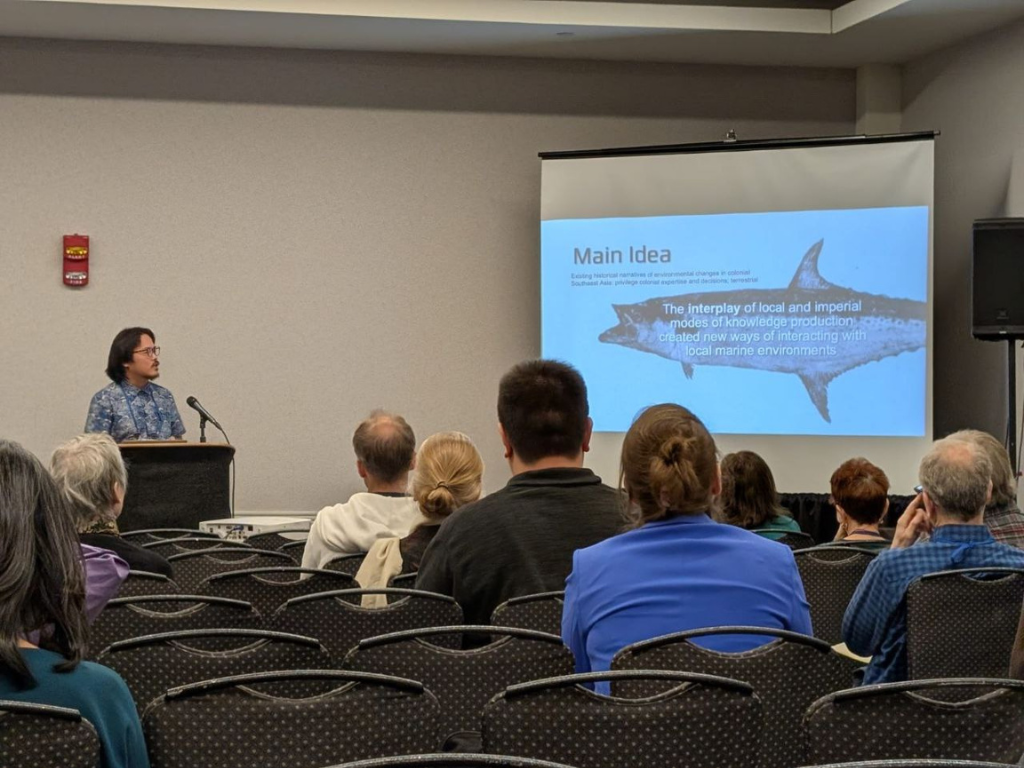

Ruizhi presenting his paper, “Of Ikan & Ichthyology: Local & Imperial Knowledge Production in Malayan Fisheries, 1921-1942″ as part of a panel featuring “Rising Voices in Southeast Asian Studies: Southeast Asians in the Anthropocene” at the Association for Asian Studies conference. Source: Ruizhi Choo

Wait, so, how did he get into this?

Before going full entomologist-historian, Ruizhi’s master’s research was on fish. He explored the history of fisheries in Malaya as well as coastal economies, fishing communities, and marine ecosystems.

“There wasn’t a lot of work on people’s relationship with the sea,” he says. “But I’ve always been drawn to the natural world, biology, animals, ecology.”

Still, when he first joined the National University of Singapore (NUS) in 2013, he wasn’t set on history at all.

“I tried political science, sociology, literature,” Ruizhi recalls. “I thought I’d be a political scientist or sociologist. But nothing really clicked.”

Well, almost nothing. There was one subject he didn’t hate: history.

“I’ve done history in high school, and nothing really excited me in uni until I came upon a chapter in a book about tigers in colonial Singapore,” Ruizhi admits. “It was the first time I saw nature and animals being discussed in a historical context. I didn’t realise you could study that kind of history.”

Ruizhi and his academic advisor, Professor Leonard Andaya. Source: Ruizhi Choo

The path became clearer, and the rest was history (no pun intended).

Ruizhi completed his BA in History at NUS, followed by a master’s degree, graduating in 2019 with the prestigious Wang Gungwu Medal and Prize for the best thesis in the Humanities and Social Sciences.

After graduation, Ruizhi worked as a senior analyst at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. It was a crash course in real-world relevance and how history intersects with policy, security, and current events.

“That job helped me see that history isn’t just about the past,” he says. “It shapes how we think today, how we govern, how we respond to challenges, even environmental ones.”

Academia came calling again.

Ruizhi wanted to dive deeper into Southeast Asia’s environmental past, and that meant pursuing a PhD in History. In 2023, he moved to the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where he’s now approximately halfway through his History PhD.

Ruizhi is also a graduate teaching assistant at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, teaching and leading weekly lab sessions in World History courses, such as Global Environmental History and World History of Human Diseases. Source: Ruizhi Choo

Why Hawai’i, though?

You might wonder — if his research is about Malaya, why not stay in Singapore?

I took classes with Professor Leonard Andaya when he was guest-teaching at NUS in 2018, and he was the one who first asked if I’d consider doing a PhD,” Ruizhi says. “At the time, I wasn’t ready — but after working for a few years, I wrote to him. He was happy to be my advisor.”

The best part? The University of Hawai’i at Manoa has a very comprehensive Southeast Asian programme and the Centre for Southeast Asian Studies. That’s not all; it is also home to a vibrant community of Southeast Asian students.

Ruizhi is now Andaya’s final student. It’s a full-circle moment — and a fitting mentorship for a researcher delving into the overlooked corners of Southeast Asian history.